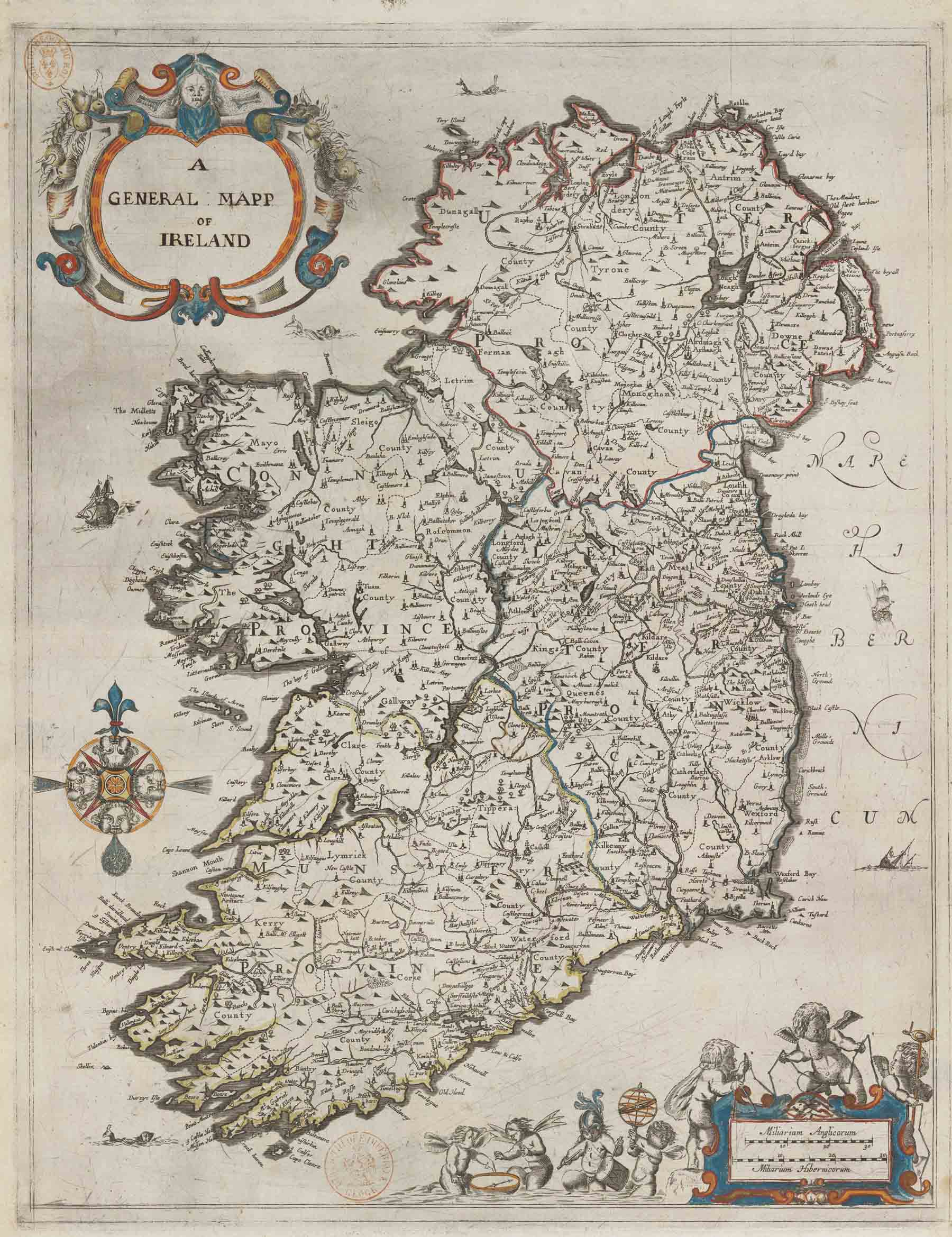

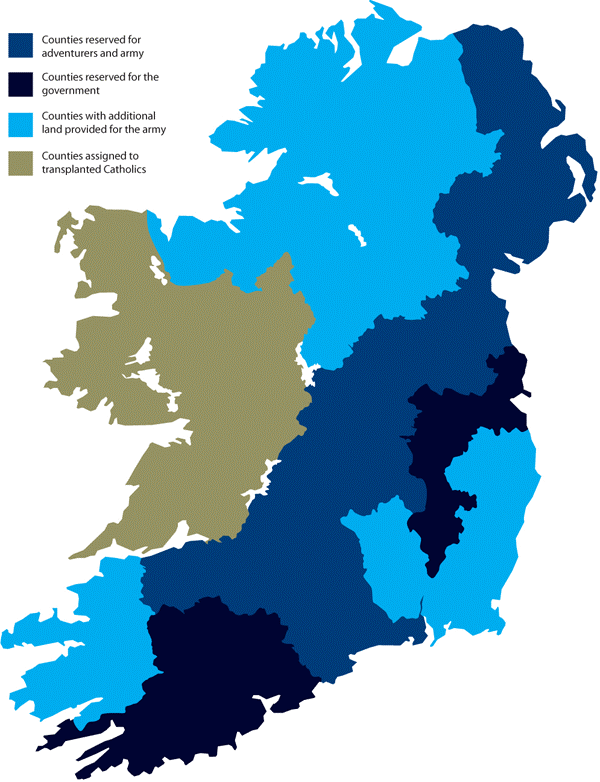

In July 1653, the Commonwealth regime issued an order for the transplantation the following year of Catholic landowners across the Shannon to Connacht, the most isolated and poorest of the four Irish provinces. This order targeted thousands of landowners and their dependants but even the most recent research on the topic has failed to produce accurate figures for the numbers who actually moved into Connacht. Catholics, however, no longer retained any land east of the Shannon. In September 1653, two months after the transplantation order, the English parliament passed the Act of Satisfaction, which began the process of distributing forfeited lands among the adventurers and disbanded soldiers. In the first instance, the land would have to be accurately surveyed.

Cromwellian Land Surveys

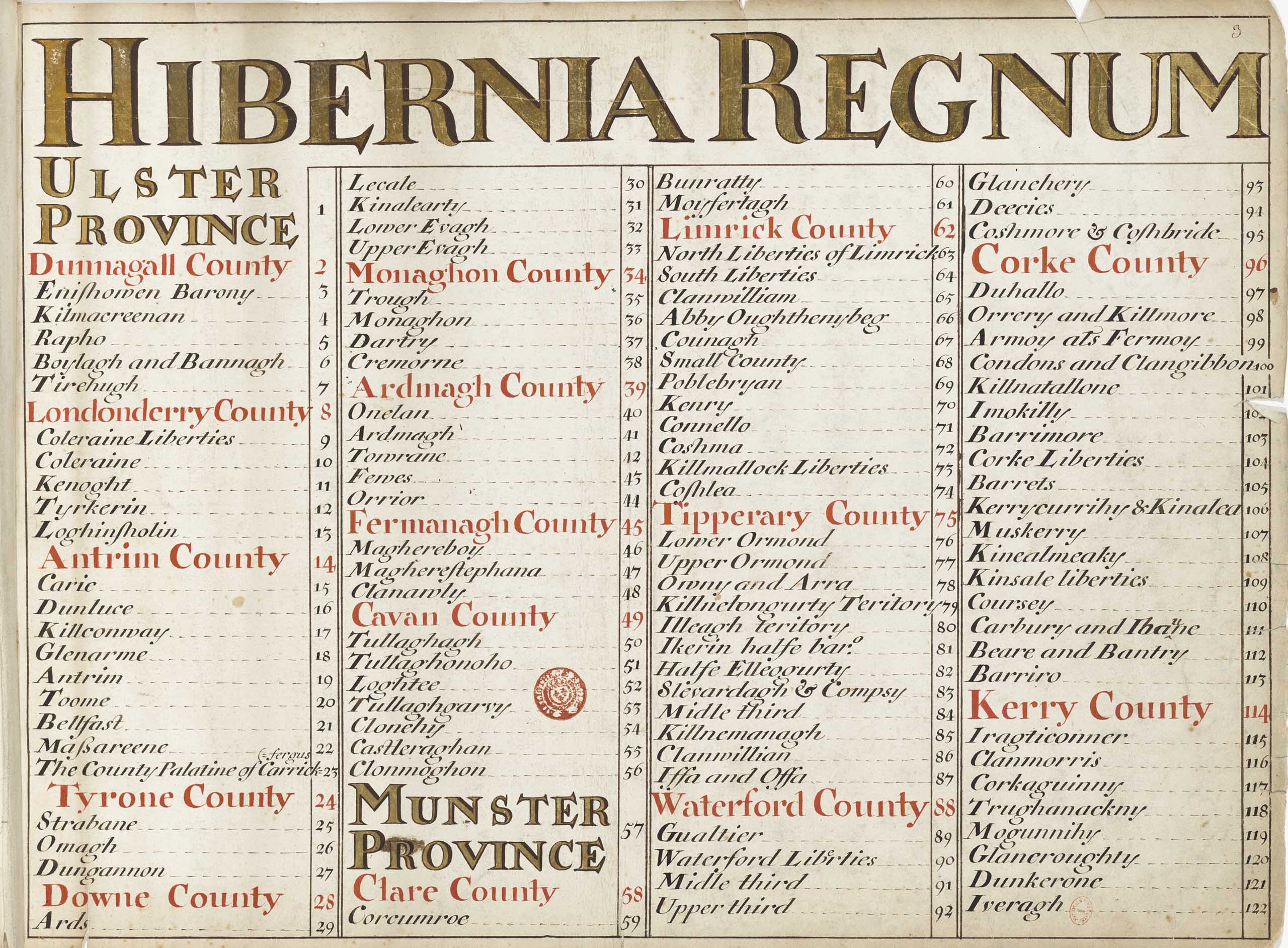

On 26 September 1653 the ‘Act for Satisfaction of Soldiers and Adventurers’ commissioned the ‘Gross and Brief Survey’, which surveyed forfeited lands in counties Limerick, Tipperary and Waterford in Munster; Laois, Offaly, Meath and Westmeath in Leinster and finally Down, Antrim and Armagh in Ulster. The primary purpose of the Gross Survey, undertaken by Benjamin Worsley as Surveyor General of Ireland, was to provide a rough estimate of the area of forfeited land available in each barony (hence the name ‘Gross Survey’) and to determine the ownership of each estate. Little of the Gross Survey survives but a fragment for the town of Mullingar, in County Westmeath, is dated 3 October 1653.

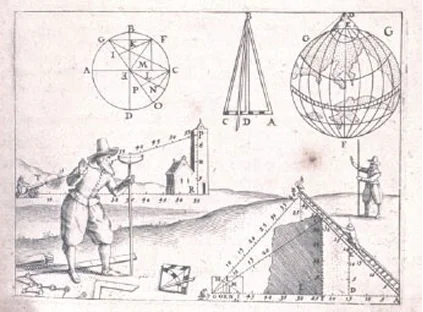

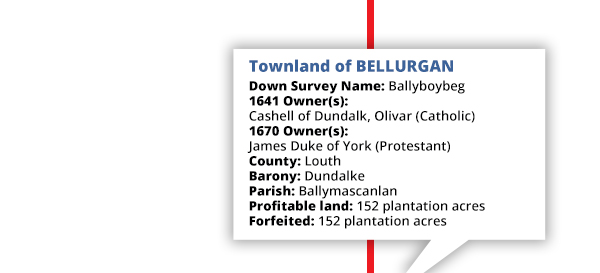

The land identified by the Gross Survey did indeed prove insufficient to satisfy all claims, so a commission to undertake a second, more ambitious survey was awarded to Worsley on 14 April 1654, not by the army but by the civil authorities in Dublin, hence the name ‘Civil Survey’. Whereas the Gross survey focussed on ten counties (plus Louth), the Civil Survey eventually covered much of the country, to provide for additional claims, principally from thousands of army officers and soldiers, but also from government officials and anybody else seeking compensation from the state. The so-called Strafford Survey from the 1630s, undertaken at the behest of Lord Deputy Wentworth, was used for the province of Connacht. Surveyors established the ownership of every townland, identified the lands to be forfeited and estimated (but did not measure) the extent and value of each estate. The scope of the Civil Survey indicates that its primary purpose was to determine the greatest amount of possible forfeitures. In the end, the redistribution of Catholic estates, which comprised over half of the land in Ireland, proved sufficient.

To counter the adventurers’ domination of the surveying process, the army lobbied in late 1654 for the appointment of William Petty, an army surgeon and personal physician to Oliver Cromwell’s son, Henry, to be the surveyor of forfeited lands. The army did not accept the estimates provided by the Civil Survey, believing them to be widely inaccurate, and Petty embarked on a defamatory campaign against Worsley, describing his rival as a con-man who had moved to Ireland to ‘repair himself upon a less knowing and more credulous people’. On 8 September 1654, therefore, only three months after work on the Civil Survey had begun, the authorities in Dublin appointed a Committee of Surveys, chaired by Colonel Hardress Waller and dominated by army supporters. The committee reported that the methods adopted by the Civil Survey would lead to many disputes and made the case for a more exact survey, by measurement. Petty claimed he could produce such a survey within one year and by December 1654, despite Worsley’s objections, Petty received a contract for a new survey, which unlike the Civil Survey would not only accurately measure all forfeited land but also provide accompanying maps. For the moment, both surveys would continue in parallel, but tensions between the two men continued to fester and the Civil Survey was finally abandoned in 1656. Worsley left office the following year, leaving Petty in sole control of the surveying process and the subsequent redistribution of land.

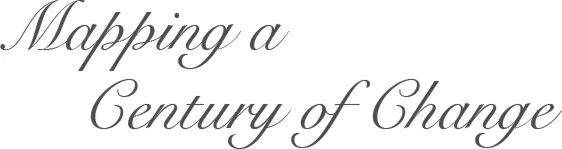

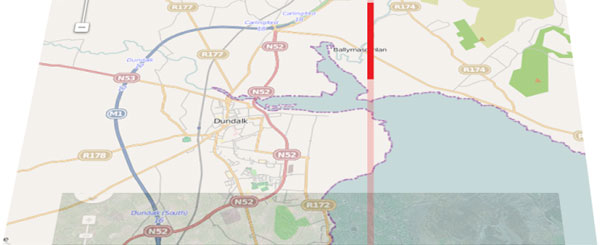

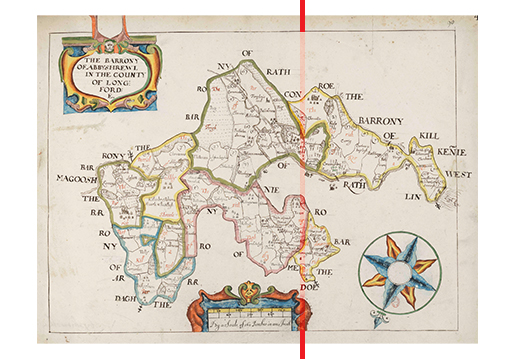

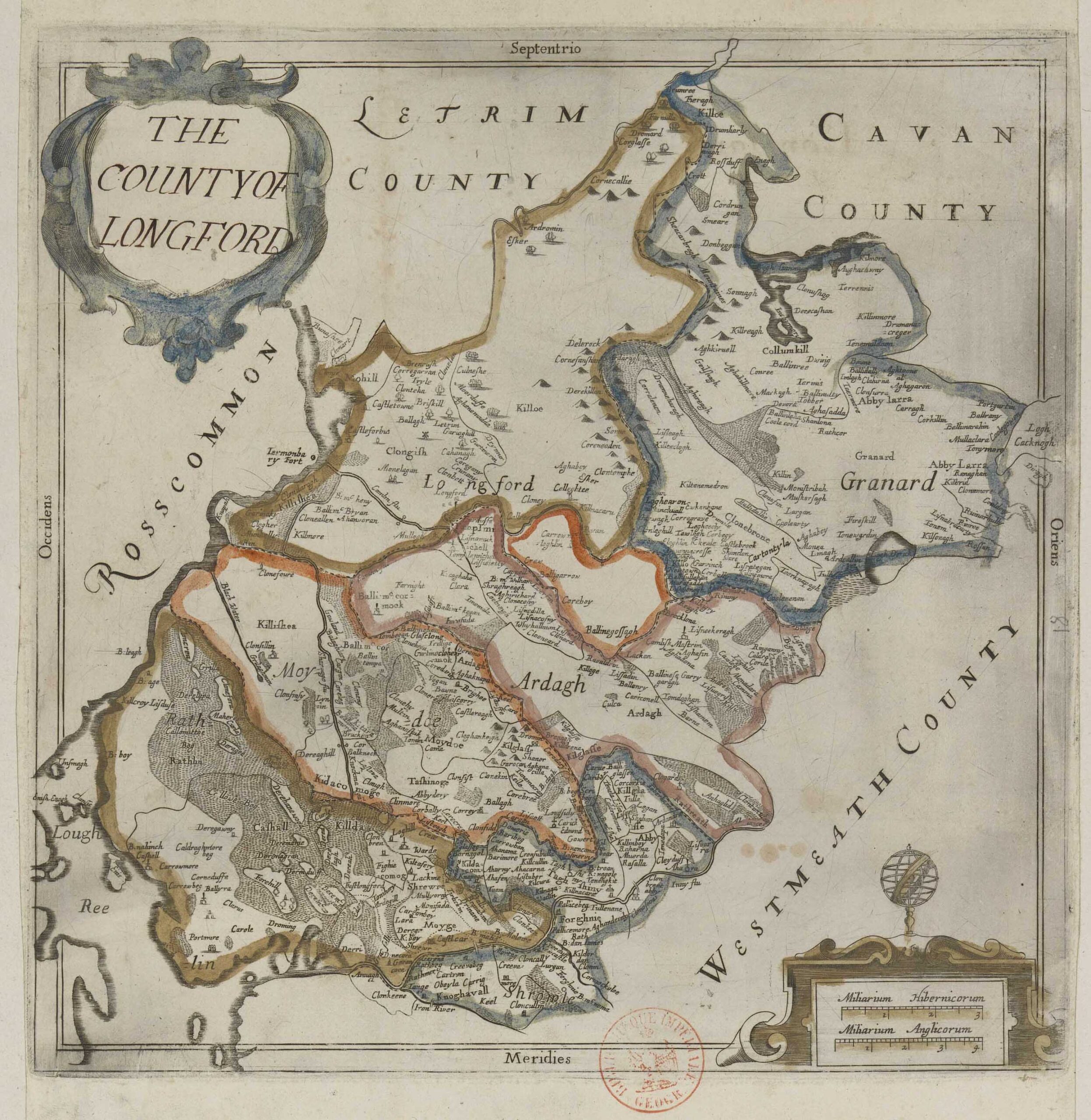

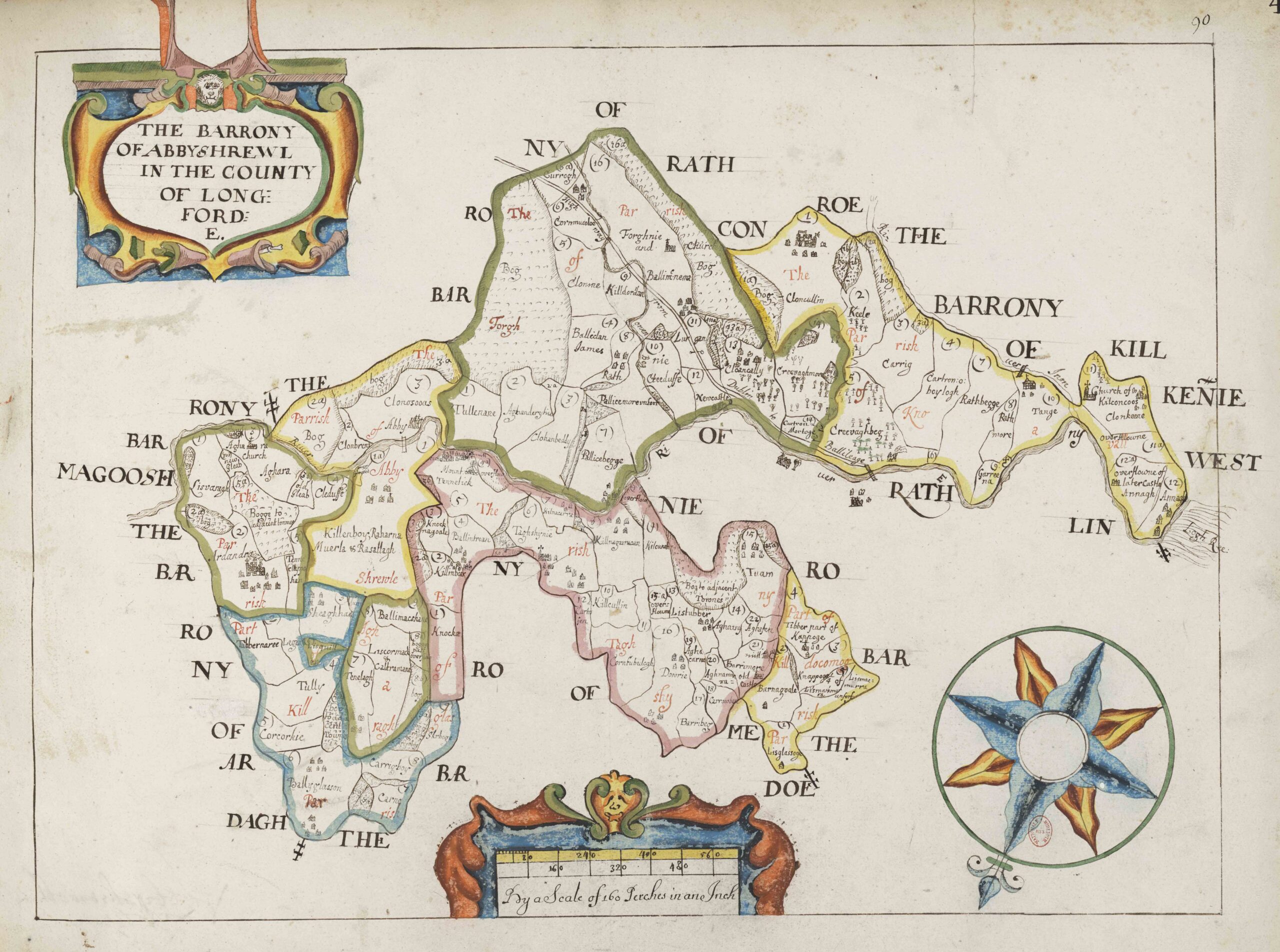

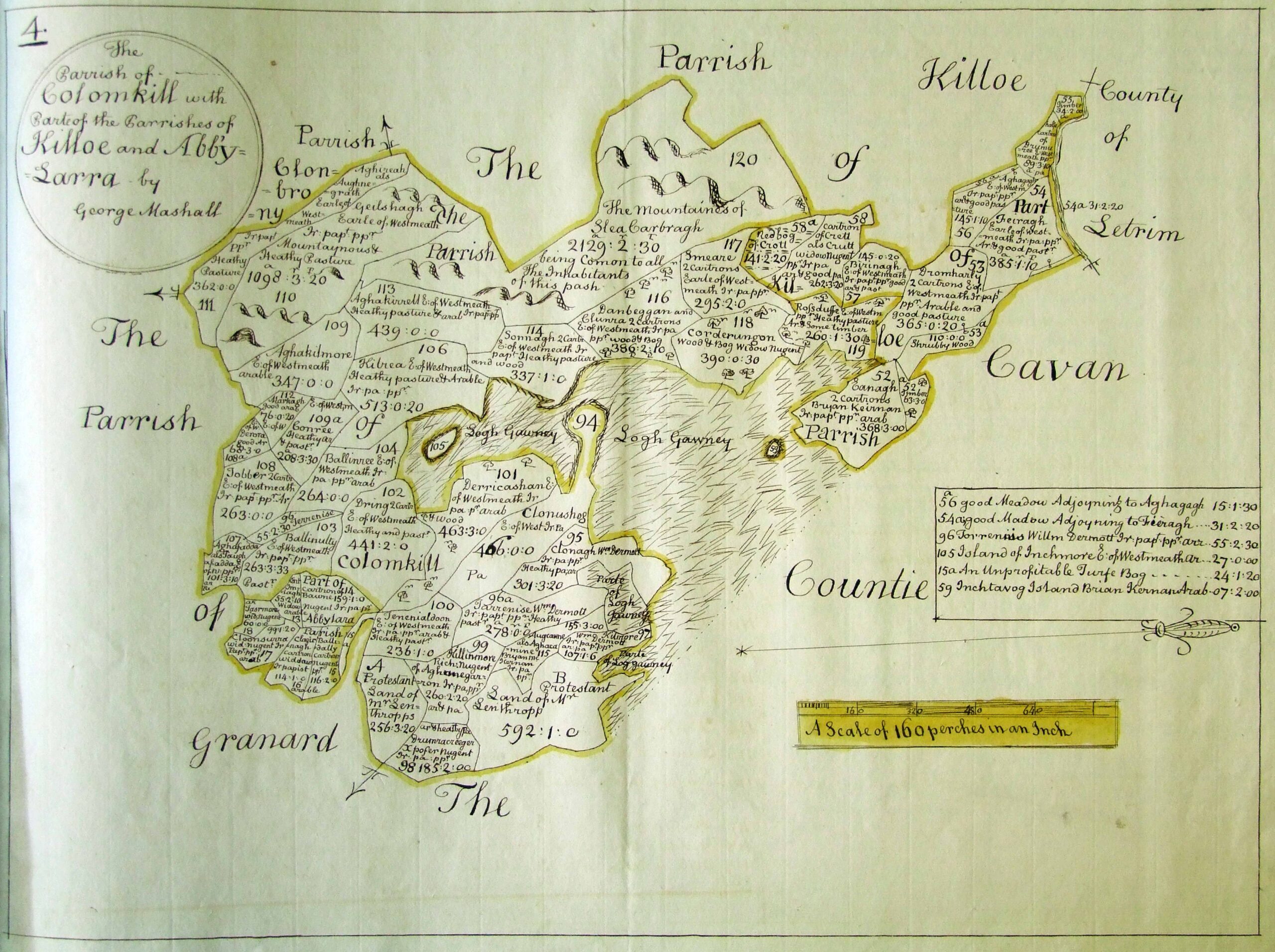

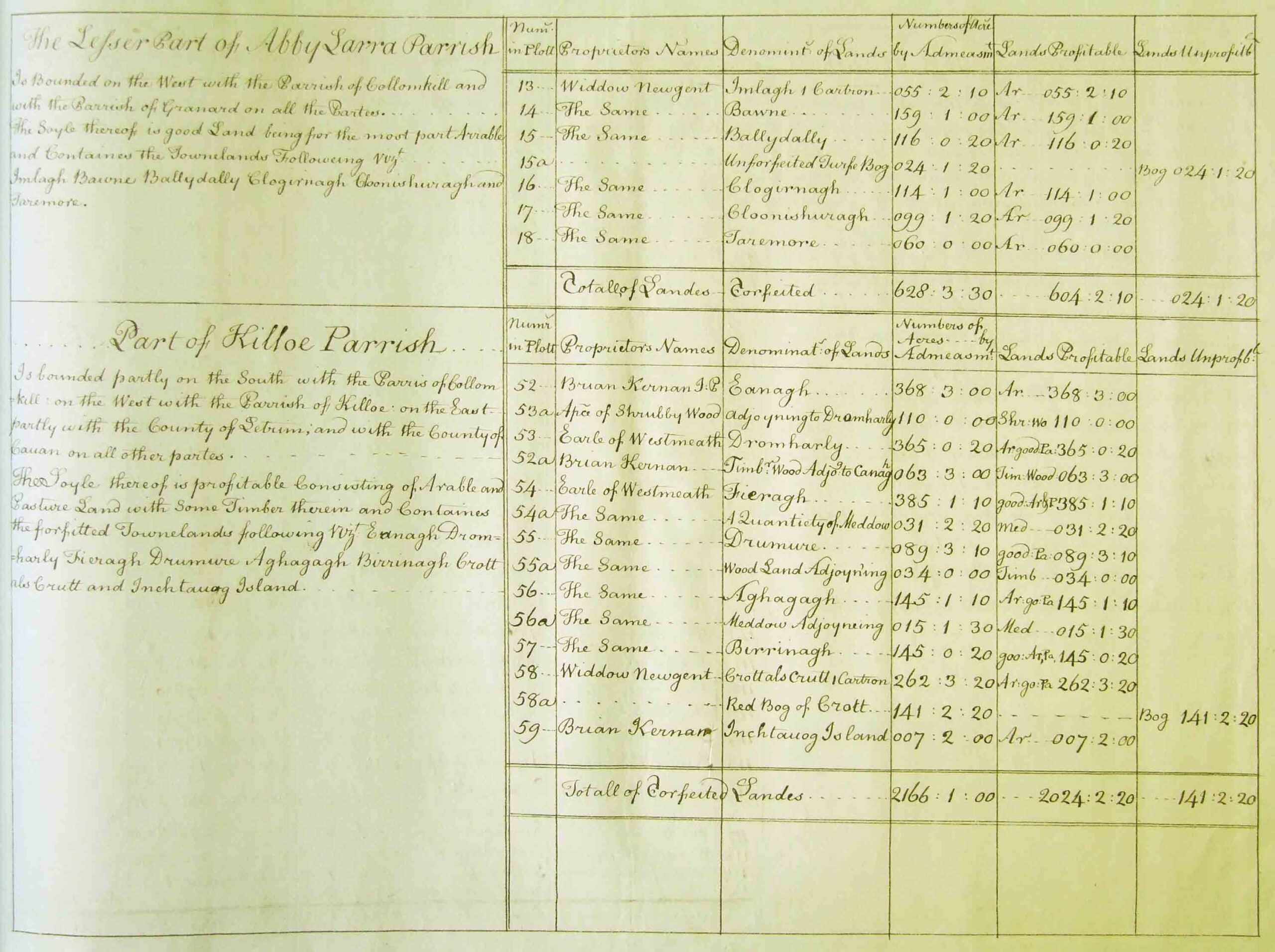

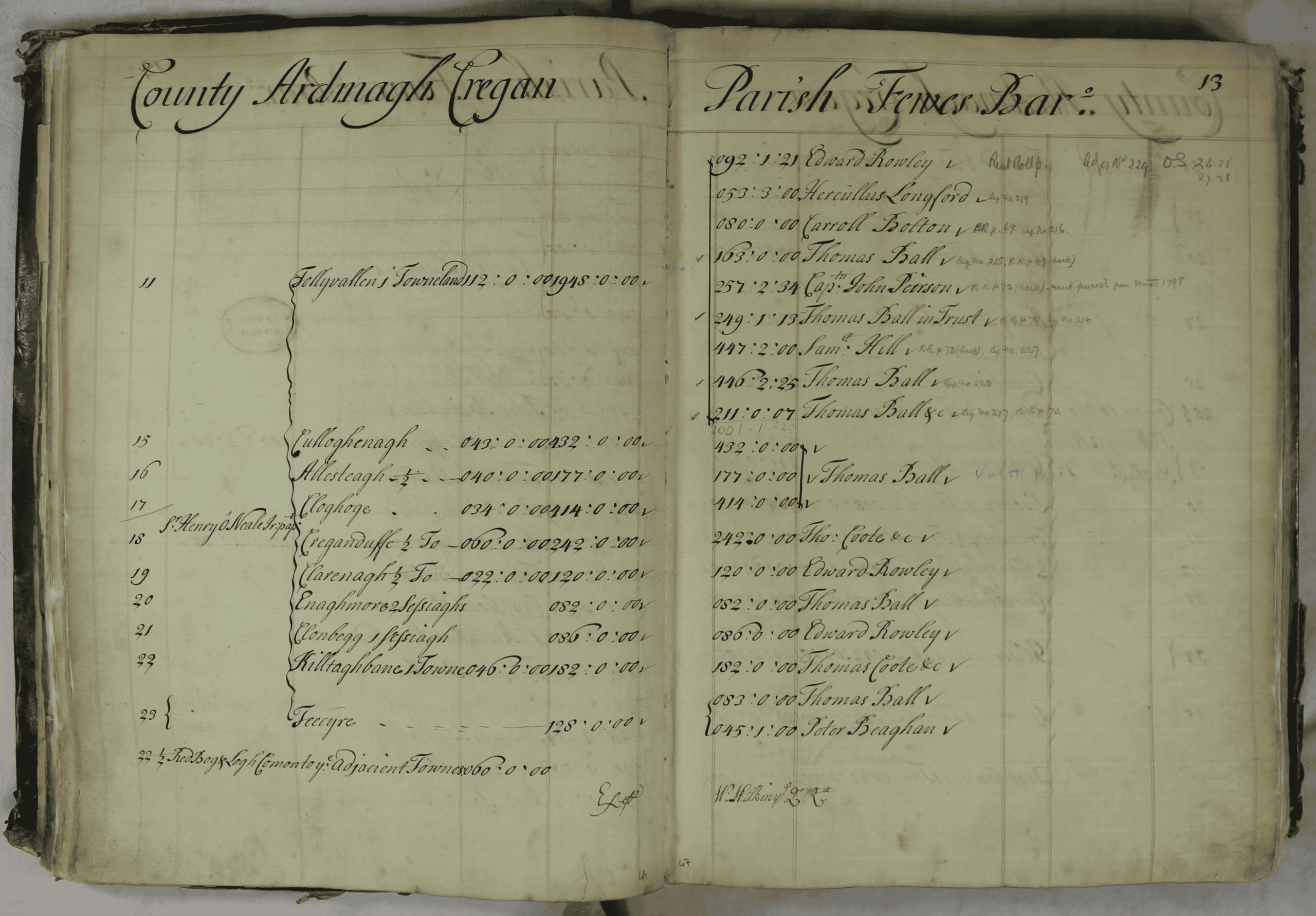

Petty’s survey, later called the Down Survey, because ‘a chain was laid down and a scale made’, was the third and final survey of the land allocation process. Using the Civil Survey as a guide, teams of soldier-surveyors, working parish by parish, set out to measure every townland to be redistributed to soldiers and adventurers. The resulting cadastral maps, made at a scale of 40 Irish perches to one inch (the modern equivalent of 1:10,000), are unique for the time. Nothing as systematic or on such a large scale exists anywhere else in the world during the early modern period. The primary purpose of these maps was to record the boundaries of each townland and to calculate their areas with great precision but they are also rich in other detail, showing churches, roads, rivers, castles, houses and fortifications in addition to all the principal topographical features. The survey was restricted to forfeited land in Ulster, Leinster and most of Munster, relying on the Strafford Survey for coverage of Connacht, Clare and north Tipperary. Nonetheless, the forfeited lands measured by Petty, alongside all other available material, made up roughly half the surface area of Ireland, providing essentially a survey of catholic estates, not of the entire island.

The Down Survey remains the monumental achievement of early modern cartography, not only in terms of its ambition, scale and speed of execution but also the accuracy of the results. An analysis of sample townlands in the survey, where a direct comparison can be made with modern measurements, shows an average deficiency of just over 11.5%, a truly remarkable figure given the primitive nature of the surveying tools and the difficult conditions faced by the surveyors. Petty’s organisational genius can leave the impression that the survey and subsequent distribution of land proceeded in a transparent and orderly manner but the reality proved very different. It quickly became apparent that the government intended to give away a huge amount of land in Ireland to anyone who could make a plausible case for compensation. Indeed, the Act of Satisfaction in 1653 included a provision that any forfeited land not required for soldiers and adventurers could be used to settle public debt. The Committee of Adventurers, sitting in London and working completely independently of the Committee of Surveys in Dublin, freely exchanged debts due to army officers for service in England in return for forfeited land in Ireland. The Council of State in London also received numerous petitions seeking Irish land in compensation for damages relating to the English civil wars. The constant exchange of land on the basis of scraps of paper and receipts of increasingly dubious legal validity, led to a serious decline in property values. Such was the untidy reality of the Cromwellian land settlement.

Upon its completion in 1659 the Down Survey was housed in Dublin, along with the Strafford Survey, in the care of Worsley’s successor as Surveyor General, Vincent Gookin. The maps and accompanying terriers (textual descriptions) were bound into volumes and made available for public consultation until the destruction of a large amount of the material in an accidental fire in the old records office in Dublin in 1711. The Down Survey survived in its entirety for ten counties – Derry, Donegal, Tyrone (Ulster); Carlow, Dublin, Westmeath, Wexford and Wicklow (Leinster); Leitrim (Connacht) Waterford (Munster) – while the volumes for Clare and Kerry (Munster); Galway and Roscommon (Connacht) were completely destroyed. Partial papers survived for the rest. All the surviving original maps were finally destroyed in 1922, when Free State forces bombarded the Four Courts. Numerous copies, however, were made between 1711 and 1922. In 1786 Daniel O’Brien copied those maps bound in books that had survived the fire in reasonably good order and this collection was purchased in two lots in 1965 by the National Library of Ireland and the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland. These manuscripts form the bulk of the parish maps and terriers now available to the public on the Down Survey website.